A forthcoming research article, (and now published) by Carlos Berdejó a professor of Law at Loyola of Los Angeles who also has a PhD in economics, has documented racial disparities in the plea bargaining process in Dane County, Wisconsin (home of the University of Wisconsin – Madison) in the years 2000-2006. While the data from this study are now over 10 years old, this will motivate local people to take a closer look at plea bargaining here, as well as call attention to the plea bargaining process everywhere.

The data come from CCAP, the computerized court record system. Berdejó found that although there was no racial difference in how people charged with serious felonies were treated, there were large racial differences in how people charged with their first misdemeanor were treated, and significant racial differences in treatment for low-level felonies. He also found that the racial differences were largest for first offenders, while the racial differences for people with prior convictions were small. He concludes that prosecutors seems to be treating Blacks with no prior convictions as somehow inherently more criminal than Whites with similar records.

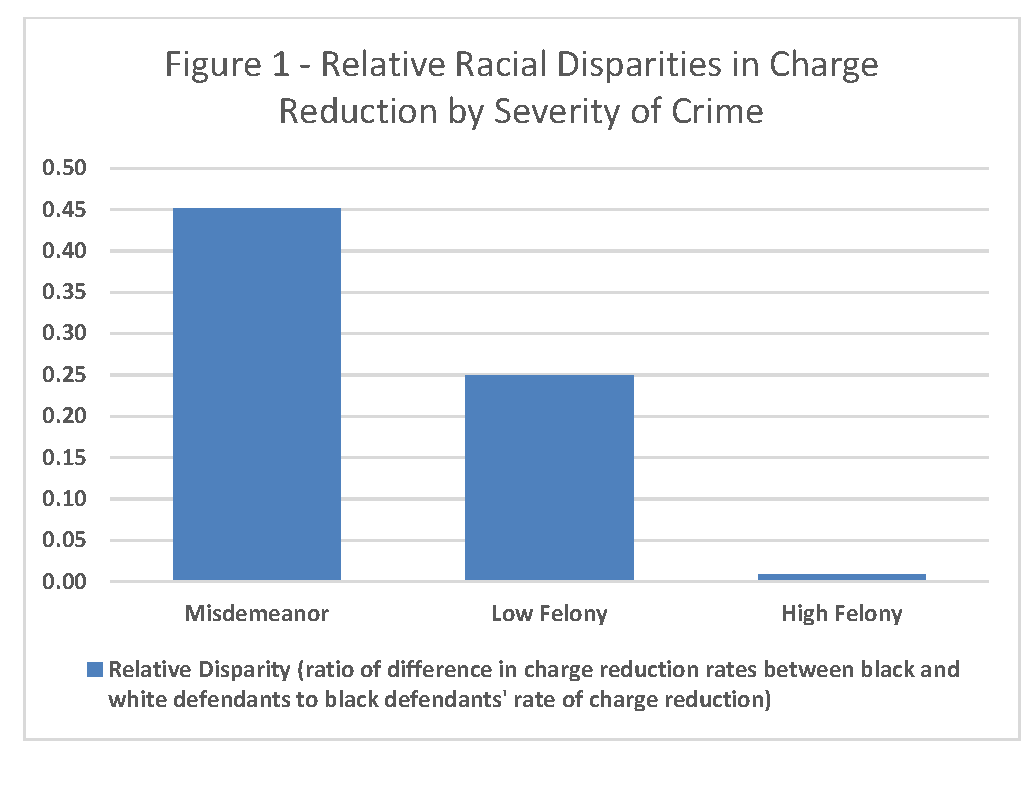

The largest proportional difference is that Whites were 75% more likely than Blacks (37% of White defendants vs. 21% of Black defendants) to have all misdemeanor charges dropped or amended to lesser charges that might carry a risk of a jail or prison sentence (table 3A). Some of this difference is due to prior records, but even looking only at people who had no prior convictions, Whites were 46% more likely than Blacks to have all misdemeanor charges dropped that risked incarceration (58% for Whites vs. 39% for Blacks, Table 4), and there substantial racial differences in misdemeanor plea bargaining for those with prior convictions as well.

There were smaller but significant differences in charge reductions for lesser felonies (defined as those having a maximum sentence of five years in prison), where Whites were 25% more likely to experience a reduction in charges. Moreover, among those with no prior conviction, Whites originally charged with a lesser felony were 22% more likely than Blacks to have all felony charges dropped (59% for Whites vs. 48% for Blacks, table 4).

This study also found racial disparities in sentencing, with more use of incarceration sentences for Blacks than Whites and, when sentenced to incarceration, slightly longer sentence lengths. Berdejó believes these differences were due to judicial discretion, although I learned informally through my interactions with local prosecutors, judges, and public defenders that the custom in Dane County was that sentences were never argued before the judge, so that the judge nearly always just ratified the sentence recommendation from the plea bargain.

Multivariate analyses reported in the article show significant race effects on charge reductions after controls for specific crime characteristics, prior convictions, sex, age, and concurrent charges. Separate analyses also check for the effects of specific prosecutors and defense attorneys. These “controls” for prosecutors and defense attorneys did not say whether the controls added significant explanatory power. I have always wondered whether there were attorney effects. Rumors at the time suggested there were some assistant district attorneys in the prosecutor’s office who were especially problematic about racial issues. And it is widely believed that there are differences in quality among the three classes of defense attorneys: public defenders, private attorneys paid by the client, and court-appointed attorneys. Also, misdemeanor offenders who cannot afford an attorney are not provided one for free. One wonders whether not having an attorney at all might be a big factor in the misdemeanor cases.

Having debated these issues with judges and prosecutors for years, I can also report that they insist that prosecutors may have access to juvenile records or records from other states that would justify differential treatment and that using Wisconsin’s court records to identify previous records is inadequate. I have always found these arguments to be frustrating, as they use unverifiable claims about hidden data as an excuse to ignore actual empirical data about how their own systems operate, but I will make this point so others know I have heard it.

The author apparently knows little about Wisconsin’s racial disparities or its politics. He says in the article that he decided to study Dane County instead of Milwaukee County because he seemed to think Dane would be more typical of the rest of the state. By most measures, bad as it is, Milwaukee County is less racially disparate in its criminal justice statistics than Dane County, and Dane County is one of the most disparate counties in the country, so his arguments for choosing Dane as somehow more typical of the US were probably misguided, although his choice makes the study of greater local interest.

The treatment of first offenders on lesser charges is where racial disparities in processing after arrest show up most often. In the early 2000s, I got involved with an advisory committee working to reduce racial disparities in juvenile criminal justice and worked with an assistant district attorney who was sure White juveniles were being treated differently by prosecutors than Black juveniles. She organized a study of the charging decisions for two months and we did, indeed, find evidence that White juveniles were more likely to have charges lowered or dropped between arrest and formal charging, but this study was too small to provide any definitive data. In this small study, we also found that Black juveniles generally first showed up in the criminal records with low-level misdemeanors, while White juveniles often first appeared as a felony. We asked, did anybody think those Whites kids were not doing bad things before their felony? Nobody did. Instead they thought that White kids were being warned and released for their actions, or handled through suburban municipal courts rather than referred to the county circuit court for criminal charges.

For a news blog about this study see the Marshall Project.

One comment